The Famous 1881 Debate - Key Issues

While in popular folklore, the grate debate between Father John O'Leary and William Bence Jones is often mentioned, and particularly as it have rise to the well known ballad 'The Wife of the Bold Tenant Farmer', nobody, as far as we know, has attempted to examine the key issues of the controversy itself. This examination, which does not claim to be definitive, is based on the main sources available, namely the autobiography of Bence Jones, published in December, 1880, entitled "A Life's Work in Ireland', containing the original assault on Father O'Leary and the Land League, and the three subsequent articles in 'The Contemporary Review' of London, which the 'Skibbereen Eagle' also re-published. These articles were titled - 'Mr. Bence Jones' Experiences in Ireland' by Father O'Leary (June 15th, 1881), 'My Answer to Opponents' by Bence Jones (July 15, 1881) and 'Mr. Bence Jones' Answer to Opponents Examined' (September, 1881)

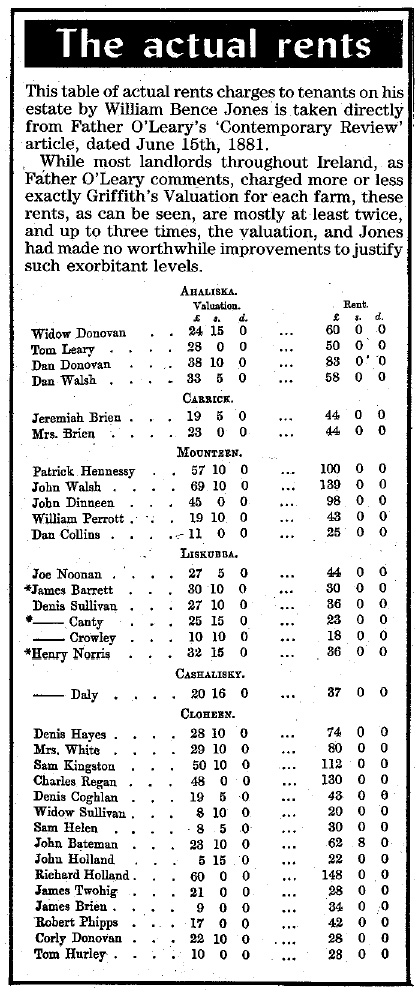

"The series of articles contributed

by Rev. Monsignor John O'Leary to the 'Contemporary Review' created almost a

sensation in England at the time and made so deep an impression in high quarters

that among others Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone, wrote warmly

congratulating him on his brilliant indictment of Irish landlordism.".

When Monsignor O'Leary, first chairman of the Southern Star Company Limited,

died in November 1921, the 'Dublin Evening Telegraph' carried an obituary of him

containing the above words and while we have dealt elsewhere in this Centenary

Supplement, in a general fashion, with the controversy involving the Clonakilty

P.P. and William Bence Jones of Lisselane as the 'Evening Telegraph' call him in

the same piece 'that greatest landlord scourge in the South of Ireland, that

typical racket-renter and exterminator, whose name became a byword throughout

the land,' no core details of the dispute were cited in our other article.

The general setting and background to the landlord and tenant question, the

significant comparison with England and Ulster (to Southern Irish advantage) as

well as a resume of the Land League agitation and the early Land Acts were given

in that article, so here it is only necessary to summarise the particular

dispute involving Monsignor O'Leary and Bence Jones because not to do so would

leave readers with only a sketchy account of exactly why this altercation was so

butter and why it was so important nationally as well as in a British and

Ireland context.

A major work in 1880

Irish landlords in that terrible

19th century dominated by the Great Famine and other pestilences, rarely, if

ever, rushed into print, except for letters to newspapers, to attempt to

vindicate their doings, but one who did publish a 'major work' a book of 338

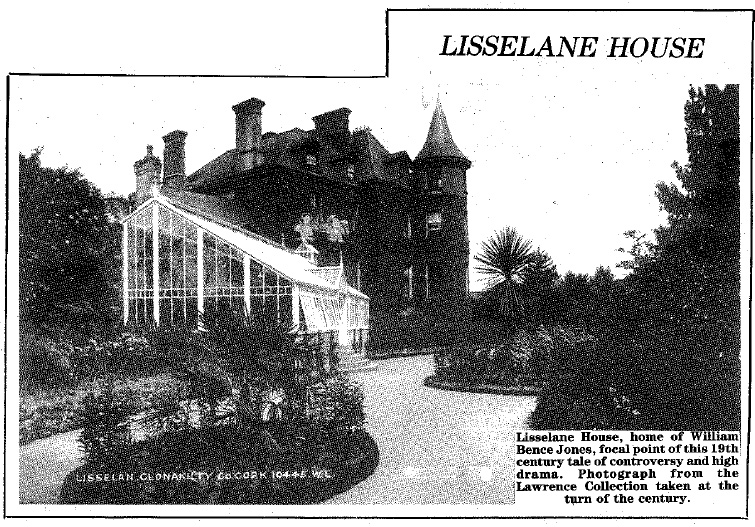

pages, published in London by MacMillan and Co. in 1880 was this William

Bence Jones of Lisselane, Clonakilty.

The title as mentioned elsewhere was "Life's Work in Ireland or a Landlord Who

Tried to do Hid Duty' and though detailing various stages in his Irish career,

from arrival in 1840 to date of publication, 1880, the main thrust, as detailed

in the preface, is directed at the Land League and particularly at the person of

Father O'Leary, then curate in Clonakilty.

That Bence Jones, alone of the Irish landlord class, went to such trouble and

expense, must have said something for his sense of guilt and his pressing need

to exonerate himself before the eyes of, particularly, his peers. Yet, his very

rushing into print was perhaps his greatest mistake because if he were akin to

'good' landlords, who, as in England, did not hold land for exorbitant profit,

his case would have been defensible. Unluckily for him, Bence Jones encountered

an opponent of the calibre, intelligence and moral courage of Father O'Leary and

that was his undoing.

Having lost the argument, in the end, Bence Jones also turned on his peers.

According to Father O'Leary's final foray in the 'Contemporary Review'

(September, 1881), Bence Jones not only imputed 'bad and unworthy motives' to

himself but also to 'the New York Herald, the Standard newspaper - and to Mr.

Gladstone and the chief members of the present Cabinet.'

Bence Jones also came badly unstuck in his attempts to portray Father O'Leary as

an 'ignorant man' associated with 'inferior townspeople,' a man 'discreditable

to the Roman Catholic Church' and a man without friends.

That Father O'Leary had plenty friends, and very reputable ones at that, had

been quickly proved in these same months when the people of Clonakilty got

together to present him with the testimonial that, having been lost on a number

of occasions, down through the years, was eventually found and now has an

honoured place in the West Cork Museum in Clonakilty.

Testimonial to Father O'Leary

Arising mainly from his work with

the Land League, this testimonial was presented to Father O'Leary at a public

meeting in the Town Hall, Clonakilty, in August, 1881 and presiding was the

chairman of the Town Commissioners, Daniel O'Leary and present also were the

other town commissioners as well as such well-know personages as T.J. Canty,

Callaghan McCarthy and Thomas Hurley T.C. who made an emotional speech in favor

of Father O'Leary.

Bence Jones has stated according to Thomas Hurley, that Father O'Leary had no

friends in Clonakilty and that the Land League contained no 'respectable people'

so 'this testimonial would let Mr. Bence Jones see the friends of Father O'Leary

and the estimation in which he is held by all creeds' and so 'the lie is put

down the throat of Bence Jones.'

'Father O' Leary,' he added 'was beloved of all parties without distinction of

class or creed' while Bence Jones 'abuses everyone, ministers as well as

priests, Protestants as well as Catholics alike, he spared no one. He

represented the Irishmen as lazy drunken rogues and the women as dirty drudges.'

John Hurley went on to praise Father O'Leary's 'manliness and pluck in exposing

him and 'clearly proving to the English people and the world that Mr. Bence

Jones was deceiving them, that he was a rack renting, exterminating landlord, a

tyrant and a slanderer of the Irish people.'

Many honours were in fact showered on Father O'Leary from his own kith and kin

as when in February, 1884, a deputation travelled from Clonakilty to Skibbereen,

where he then ministered, to present him with a silver salver. Its spokesman,

Father Daniel O'Brien, on behalf of Clonakilty described him as a 'household

word for all that is truly good, honest, independent and high-souled.'

So much for an 'ignorant man' who had no friends but, as for the man substance

of our treaties, the kernel of the controversy that 'assailed' the London

'Contemporary Review' in 1881 and arising, originally from the assertions of

Bence Jones in his 'Life's work in Ireland' it has to be said that, given the

convoluted and superficially clever style of Bence Jones, and the various

accusations and denials, a short summary does not present an easy task.

Having, however, eschewed the racialist and religious bigotry, the argument,

ultimately, gets down to a series of 'case histories' involving the treatment of

particular named tenants and while the overall number was, overall many more,

the 'Contemporary Review' series deals, in the main with ten.

If this seems a small number, it should be noted that while he has 4,000 acres,

Bence Jones's total number of tenants was about forty, so the ten cited would

clearly constitute a fair representation, or cross section.

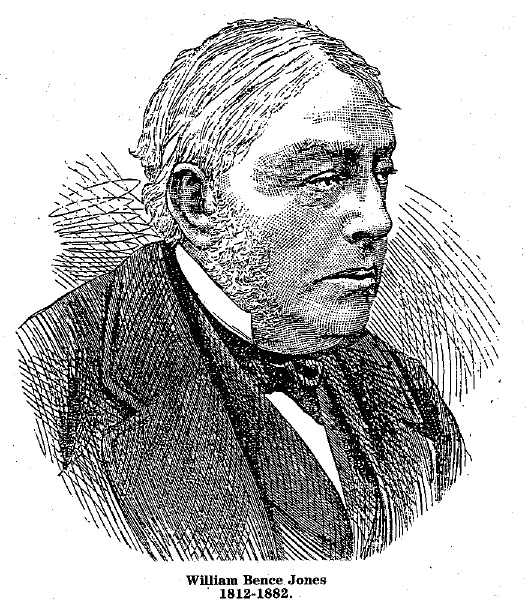

Finding a yardstick for what might constitute fair rents might

have been extremely difficult for anybody anxious to expose rack-renting

landlords, particularly if one considers obvious variations in land quality,

agricultural prices and areas of difficulty such as unimproved holdings, absence

of roads or whatever.

Fortunately for Father O'Leary, there was a yardstick and a yardstick that in

1881 was considerably more valid that it is to-day. namely Griffith's Valuation,

a monumental process of valuing all the land of Ireland carried out in the 1840s

and 1850s by Sir R. Griffith and the Ordnance Survey Department

Griffith's was fair standard

Griffith's Valuation is still the

standard for land valuation and through amended in some counties, is obviously

less than valid now, given the vast changes in agricultural conditions, but in

1881, it was still near enough as accurate as when drawn up, except, as then

stated by Mr. Greene of the Ordnance Survey, where holdings had been

considerably improved.

Where Bence Jones was concerned, however, only a few trifling improvements had

been made, so Father O'Leary was on solid enough ground when comparing his

rents, on the basis of Griffith's Valuation, with rents charged by other Irish

landlords and his first article in the 'Contemporary Review' (June 1881) appends

the rents of 32 of Bence Jones' tenants. The ones omitted were those holding

leases from before Jones had purchased the lands and being unexpired, the new

landlord was not responsible for them, whether, as Father O'Leary says, the

rents were 'low or high'

Father O'Leary cites the fact that when recently the special correspondent of

the London 'Times' visited the large and 'well-managed' estates, particularly

those of the Duke of Devonshire and Earl Fitzwilliam, the rents were 'not much

in excess of Griffith's Valuation.' Griffith's Valuation was expressed as a

certain figure for an entire holding, breaking down to so much an acre, so that

the rent could be expressed as so much an acre or so much for the entire

holding.

If the rents generally in Ireland were around the amount of Griffith's Valuation

per acre, or per holding, Father O'Leary's list was able to show that the rents

charged by Bence Jones were mostly at least twice that level and sometimes up to

three times.

Since the names will still be of interest to people living in the district

to-day. we append the full list in a separate panel and except in the case of

three marked with an asterisk, who are tenants ("on whose deaths the rents will

be considerably raised'), all of the rents are between two and three times

Griffith's Valuation.

The list shows clearly that most of Bence Jones' tenants have rents

significantly higher than Griffith's Valuation. One smallholder in Clogheen, Sam

Helen, whose valuation is £8/5/0, has a rent

of £30, more than three times the valuation,

and another smallholder, James Brien, has a rent almost four times valuation.

Even a larger tenant like Charles Regan is close on three times.

Quotation from Father O'Leary

As to comparisons between Bence

Jones and other neighbouring landlords, a paragraph from Father O'Leary's own

'Contemporary Review' article best illustrates some of the situations and

arguments employed. It reads :-

"(2) Mr. Bence Jones's rents are far higher that the rents on the

neighbouring estates. The proximity of Clogheen to the small town of Clonakilty

has been assigned by Mr. Bence Jones as a reason for charging some of the

tenants three pounds an acre - an English acre, be it always remembered - for

the land which they hold from him there. Of course contiguity to a town adds

considerably to the value of the land. But tenants who hold better land near the

town under other landlords do not pay anything like the rents extracted by Mr.

Bence Jones.

The townland of the Mills is as near to the town as Clogheen. The tenants hold

under Lord Shannon, William Gallwey holds a farm adjoining that of Charles

Regan, and nearer the town. The valuation of Gallwey's farm is

£32, the rent £24. So much for the Mills. The townland of Youghals is also held

under Lord Shannon. Mr. McCarthy holds a farm there for 26s an acre just

opposite that of Mrs. White, on whom Mr. Bence Jones raised the rent to £2 an

acre. Mr. Bence Jones states in his preface adjoining Mrs. White's let last year

at 45s 6d. This is not the case. It let at 35s 6d an acre, and Mr. Bence Jones

omits to say that the tenant who held it previously, though an exceedingly

industrious man, had to throw it up. Lord Bandon had land adjoining Kingston's

farm at Clogheen, the tenants hold at about half Kingston's rent.

Kilbree is the next last to Cashakiskey. The Andy of whom the storey is told in

p. 185 of "The Life's Work" lives there. He bought a farm last year, of which

the rent is 10s an acre. Mr. Bence Jones says it is worth 20s an acre. So that

the tenants in Kilbree hold at about half the rent which they should pay if they

were under tenants to Mr. Bence Jones. It is needless to quote further

instances."

As to evictions, the arguments used by Bence Jones, in these regards are

near to nonsensical but might sound convincing to those without knowledge of the

details and it was on this that the landlord was banking. He had not reckoned on

the likelihood of a man with the astuteness of perseverance of Father O'Leary

taking up the cudgels.

No 'tenant' he wrote, 'was ever turned out because I wished for his land. I just

took up what the tenants could not live on.' This proves, according to him, not

that the rents were too high, but that the tenants were 'incapable, lazy or

drunken.'

'I let them the land' said Jones 'at the highest rent in my opinion it was worth

to them' and further (from 'A Life's Work') he states that 'in bad years, the

utmost exertion and economy were necessary.' Yet, while there was 'terrible

grumbling,' he says of his nine tenants in Carrick in 1865 'every single man was

thriven.'

Father O'Leary's rejoinder on this point is that while he had six tenants in

Carrick in 1865, now (in 1881) 'only three of them are there to-day.' 'This,'

says Father O'Leary, 'is how every man has thriven.'

Case histories

Taking some of the 'case histories,' it is illuminating,

briefly, to examine the arguments and counter arguments by Bence Jones, on the

allegations made by Father O'Leary and we will look at six of them in order

given in the 'Contemporary Review' articles.

(1) Widow Dempsey of Clogheen. She, according to Father O'Leary, was a poor

woman who held a small farm at 17s 6d an acre and on the death of her

father-in-law, Bence Jones took away two thirds of the farm and charged almost

the same rent for the remaining one third. Mrs. Dempsey could not pay, so was

evicted with her son-in-law. On this, Bence Jones replied that Mrs. Dempsey was

a 'silly woman, with neither industry nor sense, who married her daughters worse

than badly and got rid of all he money.' He also uses the 'near to the town'

argument for the high rent and that she could have sold milk in town but Father

O'Leary replied again that 'all the Clogheen tenants could not find a market for

milk in the town.' This 'misleading argument' could not justify her rent being

raised 120 per cent, paying four times Griffith's Valuation but Bence Jones

reasons that because she lost he money she was a 'silly woman'.

(2) The Driscoll children of Carrick. Their eviction was according to Father

O'Leary, done under circumstances that 'would melt the hear of the hardest' and

without a doubt, this case is one of the 'blackest of the black' where the

reputation of Bence Jones in concerned. The O'Driscolls, a family 'much

respected in the district' were made orphans when both father and mother died,

and though a rich uncle who came back from Australia (with according to Bence

Jones a very large sum), had himself visited Lisselane House and offered to pay

their rent, Jones according to Father O'Leary 'was inexorable.' He would not

have the land in the hands of orphans (eldest boy was sixteen) and even denied

that the rich uncle offered to pay the rent. Yet, Father O'Leary, in his final

reply, states definitely that "I have it from My Hurley, the rich uncle

who brought £30,000 from Australia, that he made the offer to Mr. Jones in

Lisselane House and was told 'the land could not be left in the hands of

orphans'."

(3) Edward Lucey of Cashaliskey. Most tenants in this townland held leases not

yet run out but Edward Lucey, a 'most respectable man' held from year to year

and was suddenly informed that his rent would be raised from 14s an acre to £1.

This demand was made about 1860 but Lucey, being unable to pay was 'ejected' but

Bence Jones tries to justify it by saying that Lucey's sons successfully farmed

other land a few miles away. Father O'Leary, in replying, points out that Bence

Jones omitted to state that Lucey was told that on his death (nor remote since

was advanced in years), a further 40 per cent increase in rent would be charged

to his sons. Bence Jones is especially condescending here because he claims he

gave him extra time to consider, because 'he had a son a priest.' He was thrown

out, nonetheless.

Taking away of 70 acres

(4) Patrick Hennessy, Mounteen. There were five tenants in

Mounteen, which farm was purchased by Bence Jones about 1860 from a Mr. Hawks,

who was known for 'smart rents' and though landlords there had made no

improvements and done no more than 'fix the rents and collect them.'

Hawkes enjoyed goodwill and affection.

How did Bence Jones try to maintain this goodwill? The largest farm, 130 acres,

was held by Patrick Hennessy, at a rent of £100 but when the lease expired in

1875, Bence Jones confiscated 60 of the acres and made Hennessy pay the old rent

- £100 for the remaining 60. This was a familiar trick.

Patrick Hennessy had himself made large improvements, estimated by him to be

£700 and the custom allowed that in fixing rents, some compensation should be

made, or extra charges if the landlord had paid for the improvements. Bence

Jones did not accept this £700 estimate and insisted that improvements should be

registered according to his own estimate of £100. Is this, asks Father O'Leary

referring to the entire case, confiscation or freedom of contact?

In his reply in 'Contemporary Review,' Bence Jones argues that 'I decided it was

best for us both to leave him the good land and take away the hill' (70 acres)

Father O'Leary in his second reply, comments - 'So Mr. Bence Jones decided that

it was best for both of them to take away the 70 acres.' So he adds,' Germany

decided that it was best for them both France and himself - to take away Alsaace

and Lorraine, and so, too, Russia decided that is was best for them both -

Roumania and herself - to away Bessarabia.'

Bence Jones has also argues that Patrick Hennessy was able to give one daughter

£600 on her marriage and another daughter £150 (husband not so much approved he

hints) but Father O'Leary counters by saying these dowries were given before

1875 when the tenant was independent of the landlord because the lease had not

yet expired until that year.

Bence Jones, then, could not claim credit (as he did) for Hennessy's prosperity

up to 1875 because his lower rent had been fixed by the earlier landlord, Mr.

Hawkes. After 1875, however, with the new Bence Jones 'arrangement' even the

landlord himself, in a letter to the 'Times,' described his condition as

'shaky.'

Hennessy's position however, had been technically strengthened by the 1881 Land

Act and Father O'Leary contends that when his lease next expires in 1882, it

will not be for Bence Jones solely to 'decide what is best for them both.'

Henceforth, new leases could be scrutinised by an impartial tribunal.

(5) Hayes of Carrick. This case was quoted by Father O'Leary to show how, even

with the new Land Acts, powerful landlords could take on the law and get away

with it. Hayes, when evicted by Bence Jones went to court to get compensation

from the County Court Judge but Bence Jones pay it? No, indeed, he claimed he

was 'most unjustly treated by the County Cork judge' and on appealing at the

assizes, 'was forced on a compromise and thus got further relief.'

When Bence Jones replied in 'Contemporary Review' to Father O'Leary's

criticisms, he produced the usual stories about the degenerate Irishry,

mentioning attempted rape by the son and robbery of the fathers potato put, all

being poor excuses for an eviction.

Father O'Leary underlines this in his second reply. 'We are treated,' he says,

'to a long story about robbery and rape and learn how when ages and infirmities

had come on poor Hayes and when his sons had treated him badly, Mr. Bence Jones

came to the rescue - by rescuing the farm - and by forcing on a compromise when

the County Court Judge had given him compensation for disturbance."

(6) Dan Walsh of Ahaliska. This important example Father O'Leary describes as 'a

test case regarding rack rents.' For half a century, he says, and during the

famine years, the Walshes had paid £41 a year for a farm valued by Griffith at

£35 but on the death of Mrs. Walsh in 1880, Bence Jones sought to raise the rent

from 14s 3d to £1 an acre. The tenant complained that this 40 per cent increase

was 'harsh and vexatious' but attempting to justify it, Bence Jones contended

that over fifty years, the Walshes ('a most industrious family') has saved £820.

Father O'Leary retorts that about half of this was not attributable to farming

(dowries and other sources being cited) and he also contends that of the Walsh's

supposed 58 acres, five acres had 'been lost by a road made through the farm,'

this being the 'hardest, unkindest cut' because apart from paying for the road

in rent, same as if it were land, the tenant had to pay for making the road and

its upkeep.

So what does Bence Jones do? On finding that the Walshes are saving about £16 a

year, he 'puts on exactly an increase of rent equal to what he calculates the

yearly savings of that family had been for the past half century.'

Imagine, exclaims Father O'Leary, 'an English landlord computing the annual

profits of his tenants and adding that to the rent and during an agricultural

depression unequalled since 1848, when landlord after landlord is reducing

rents.'

'Surely,' concludes Father O'Leary, 'Bence Jones is a considerate landlord.'

In his 'Contemporary Review' reply, Bence Jones admits defeat, more or less and

is reduced to arguing about the space taken by the road, describing it as a

'great gain' and further, 'if they made good butter, instead of bad, the

difference would be double, the increased rent sought.'

To this, Father O'Leary's rejoinder is most delicate - 'only let the frog puff

himself out and he will be as big as the bullock.'

Four other similar case histories are given but these will suffice to paint the

picture. Additionally, there is a lengthy argument about the so-called 'balance

sheets' cited by Bence Jones in his "Life's Work" and Father O'Leary uses them

to turn the landlords word against himself - i.e. his sometime contention that

Irish farming was unprofitable and yet, he himself did very well out of it.

The boycotting of Bence Jones is another saga. Having head the

'Life's Work,' the English people, said Father O'Leary, were amazed to find that

Jones has been boycotted, that his labourers left his employment, that he could

not get provisions for his household in his own village of Ballinascarthy, that

his corn could not be sold in 'Orange Bandon,' that more than one steamship

company refused to convey his cattle to England and that even when they got to

Liverpool it was not east to get purchasers for them.

'What Homer have been to Achilles,' concludes Father O'Leary, the classical

scholar, 'Bence Jones has been to himself.' He seeks to 'tie up within his own

discomfiture the fair name of an ancient nation' and according to him the 'Irish

trouble is nothing else than the outcome of the low moral and social state of

the people.'

Why was Bence Jones boycotted asks Father O'Leary. 'Because,' says the

correspondent of the 'New York Herald,' ' he was the worst of Irish landlords'

but according to Bence Jones himself, it was 'because he was a good landlord.'

Amazing self-deception, assuredly, but it deceived nobody.

Bence Jones also accused Father O'Leary and the parish priest Father Mulcahy of

'drawing away his labourers' in the boycott and here he is challenged to provide

proof and fails miserably, except that some men were seen going into the P.P.s

vestry. 'Excellent logic,' retorts Father O'Leary, that a 'priest could speak to

his parishioners in his own parish.' Their treatment would take another chapter

and in Bence Jones's own book, he admits that 'in summer, they must appear in

the field, with breakfast taken, at six o'clock, with only one stop, at mid-day.

To find a closing paragraph to this terrible tale of 19th century oppression of

a mostly poor and starving people is, so myriad are the complexities of the

saga, difficult, but Father O'Leary himself provides a touching and beautifully

written, as it might be called, epitaph.

'The end of Bence Jones' life's work,' was not written when his book was

completed.' 'Another chapter remained to be added, the chapter which contained

the denouement, as unexpected as tragic, which told of the way in which he had

been repaid by the Irish people for having done his duty to them for forty

years.'

Of tragedy

"And in truth, the tale now tolerably familiar to the world, is

terrible withal. To be placed in the circumstances in which he describes himself

to have lived in Lisselane during the snows of the most inclement winter which

our generation has witnessed; circumstances, which, as he tells us, and as we

can well believe, would have tested the patience of a Job, and which is no less

that the guilty conscience of Macbeth would have murdered sleep - 'sleep that

knits up the ravelled sleeve of care' - to be placed in such a situation would

undoubtedly have been a dire retribution for the worst Pasha that ever oppressed

a province, or the most rapacious landlord that ever extorted the hard-earned

substance of the poor. And yet this victim tells us that he is a benefactor of

the people."

Bence Jones, it is clear, had, in the last two years of his life, been boycotted

and blackballed by everybody in Ireland, even by his coreligionists and while

this ancient storey, a tale of tragedy and high drama, is no longer 'tolerably

familiar to the world,' the denouement that Father O'Leary mentions is some what

unclear.

The effective imprisonment of Bence Jones in the Lisselane Castle of his own

greed, rapacity and cruelty is the likely meaning but then, like Dr. Webster of

Cork referred to elsewhere, Bence Jones also 'fled the country' for London on at

least two occasions before his death in 1882.

According to the 'Skibbereen Eagle,' he did return, probably briefly in February

1882, accompanied by his son, but then must have left again because the general

belief is that on the occasion of another return, later in that year, his death

took place aboard ship.

If the famous Captain Boycott incidents in County Mayo had not received

notoriety prior to the 1881 saga of Bence Jones and Father O'Leary, the strong

belief is that the term 'bencing' would have passed into common usage rather

than 'boycotting' and that is a true measure of William Bence Jones of Lisselane

near Ballinascarthy in West Cork.

Editor